Interviewed by Barbara McGilvray OAM

INTERVIEW SERIES

AUSIT Fellows and Italian–English translators Terry Chesher and Barbara McGilvray OAM met in the late 1970s, were foundation members of AUSIT and its NSW Branch … and were occasionally mistaken for each other. Barbara was our first interviewee in this series, and she recently reciprocated by interviewing Terry.

… we’d worked through Hell and Purgatory, but we didn’t manage to finish Paradise!

Barbara: Terry, you’ve been an active contributor to AUSIT from its very beginnings. Where does your interest in languages come from?

Terry: I’ve always liked the sound of words and languages. In my childhood (without TV or computers, let alone the internet!) I listened avidly to The Argonauts, a daily ABC wireless [radio] program for children, together with my two older siblings, and my family used to play language games in French and Latin. Apart from family, our main source of entertainment and education was the 10-volume Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedia, with chapters on literature, history, geography, art, science, nature, poetry, music and many other topics. And French! Every volume had tiny illustrated stories with the first line in French, and below that a literal translation in English but mirroring the French word order and expressions, then the last line was the correct English. Maybe that was my first experience of translation at work!

I went to a small primary school in Sydney run by Mrs Broinowski, who’d done advanced teacher training in Scotland along Montessori lines. I was excited to start learning French when I was seven, playing word games like Happy Families in French, and it was great fun. Lucky for me, because through school French was always my best subject.

In an arts degree at Sydney University Italian was my major, with tutorials where no spoken English was allowed. Why choose Italian? Partly because we had at home an illustrated copy in English of Dante’s Inferno and I wanted to read it in the original Italian. By the time we graduated we’d worked through Hell and Purgatory, but we didn’t manage to finish Paradise! We also read a major novel, Manzoni’s I Promessi Sposi, with tuition in English on Italian grammar, literature and poetry.

After graduation I was interested in translation and interpreting, but knew I wasn’t ready to work as a practitioner. I worked as secretary to the editor of the Medical Journal of Australia, and for a couple of years saved for my next goal, to attend an art history and language course in Florence. In 1962 I sailed away on an Italian ship (the cheapest way to travel to Europe), and volunteered to give basic Italian classes to Australian passengers. This helped pass the time for the five weeks it took to get to Italy. I travelled in Europe, then worked in London, and in 1963 set off for Florence to do a three-month corso superiore [advanced course] at the Università per Stranieri.

The course covered Italian language and art, with excursions and free passes to all the galleries, and I enjoyed it immensely. Just as the course finished, another stroke of good luck. A publisher turned up at the university looking for a native English speaker to translate a guidebook on Pompeii. So with the confidence of youth, I put my hand up, citing my qualifications and my lifelong interest in art history. I convinced the publisher that in Australia we spoke good English, and I got the job! They provided me with a (manual) Olivetti typewriter and the Italian text, and I typed up my translation in my pensione room. They were happy with the translation, and asked me to translate another guidebook on the Vatican City. This meant I stayed in Florence for a further three months.

Barbara: Ah, the good old days when we began our European adventures with a five-week voyage. I don’t suppose the publisher paid for you to visit Pompeii and the Vatican, so how did you go about translating those guides?

Terry: Well, I just plunged in! I’d been to Pompeii when the ship docked in Naples, and knew about its history. The guidebook was for the average tourist: about 60,000 words, with a history of Pompeii, its layout and typical houses, and the tragic volcano eruption in AD 79, with a detailed illustrated ‘Visit to the Excavations.’

The guide to the Vatican City was about the same size and had detailed descriptions and some illustrations of the fabulous works of art.

Barbara: Tell us about your career trajectory after that.

Terry: My career happened through good timing and good luck, rather than being planned.

Back in Sydney after two years abroad, I worked for an Italian organisation (ICLE) which gave loans to Italian immigrants – all men – to bring their wives or fiancées to Australia. I was interpreter for the manager, who spoke limited English, so I’d handle phone enquiries and interpret at meetings with banks, shipping companies, et cetera.

After I was married and had small children, I took on sessional work in an innovative program run by the New South Wales Health Commission. I was the Italian speaker in a group of women who each spoke one of the six major languages of immigrants in Australia in those days. We were trained as migrant health educators and held weekly sessions at various baby health centres in Sydney, helping non-English-speaking mothers to get advice from trained nurses about managing their babies’ first years. The program ran well into the late 1970s and evolved into the New South Wales Health Department’s Health Care Interpreter Service [HCIS].

It was in 1977 that both the Ethnic Affairs Commission and the HCIS were set up in New South Wales, and in other states and territories similar government services were established. Also in 1977 the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters – NAATI – came into existence. In 1978 a landmark federal government report, the Galbally Report,* recognised the need for post-arrival services for migrants, including migrant resource centres. As for training, the University of New South Wales had run a pilot training course in 1974 where I was one of the students, but it was some years before tertiary training courses were available in Australia.

*Official title: Migrant Services and Programs: Report of the Review of Post-arrival Programs and Services for Migrants, a Commonwealth Government Parliamentary Paper published in May 1978

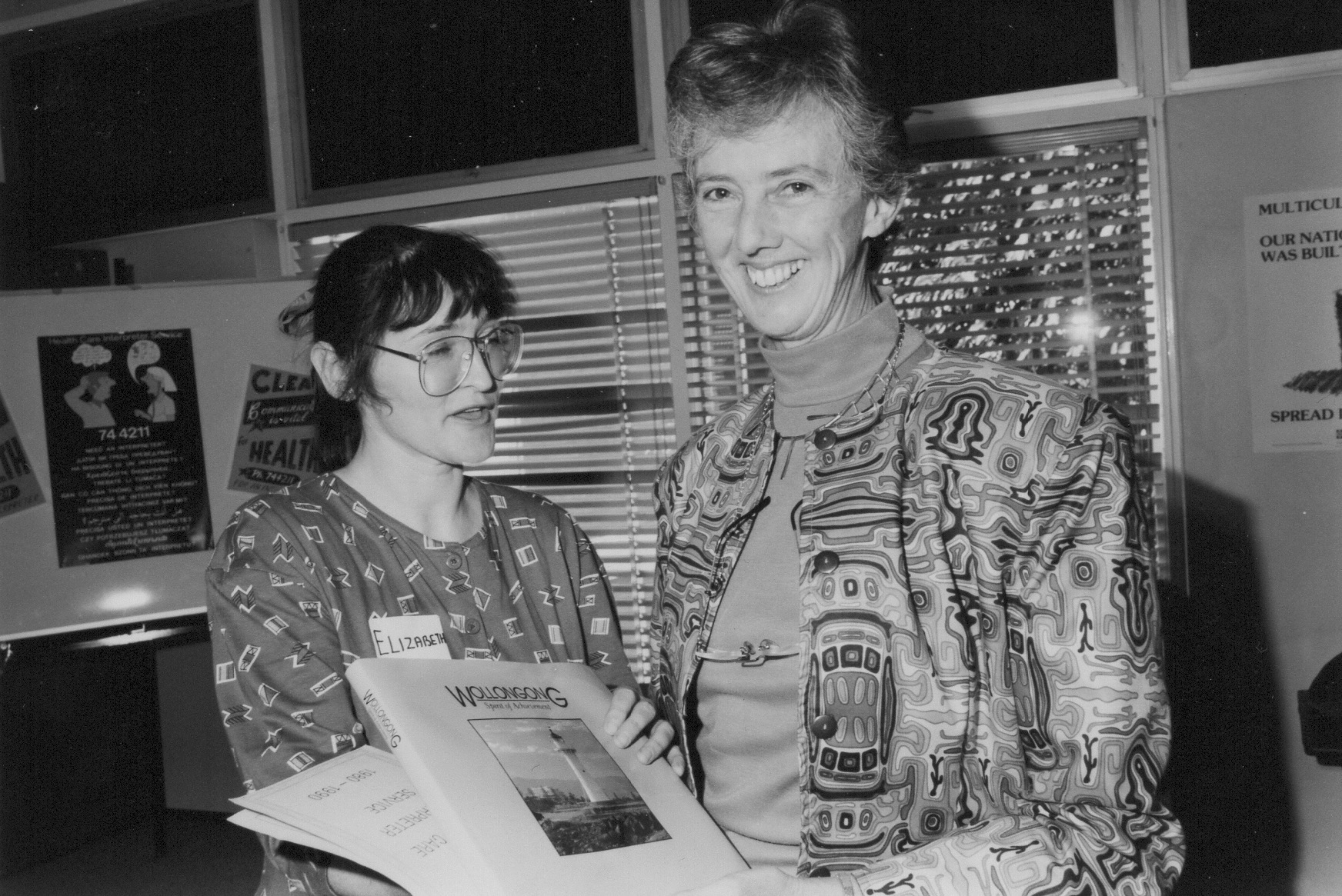

Terry was a guest speaker at the HCIS Wollongong tenth anniversary celebration in 1990. Here she is receiving a book from Liz Finch, then the Migrant Health Advisor for the Illawarra area. This photo appeared in The NSW Health Care Interpreter Service: the first forty years, published in 2017 – see below.

Pioneers Roy Richter and Lisette Engel – then Pollak – had the task of setting up the HCIS structure, administration, training course, interviews, and employment of interpreters for the Health Commission, and I was lucky to be taken on to work with them part time. A pilot program in four languages had been set up in 1974, at the Children’s Hospital in Camperdown; otherwise we were breaking new ground, and it was very exciting work. We had to conduct research to help decide which languages the first health care interpreters would work in, which hospitals they’d be based at, how they’d travel between jobs, where they’d fit into the existing hospital administrative structure and so on.

This was in 1976 and ’77, before NAATI accreditation existed. We advertised for experienced interpreters and decided to conduct role-play interviews, and devised simulated medical situations covering a range of conditions – for example, pregnant women with no English who brought their children to interpret, or patients in an emergency. We drafted tricky questions covering applicants’ attitudes to their own community, as well as cultural issues and ethical practice in health settings.

We had to find qualified bilinguals as examiners who could not only act in the role-play interviews but also assess the performance of the aspiring interpreters. In the end, 29 successful applicants started work as HCIs in 1977.

Many health professionals had never worked with interpreters, so there was training needed there too …

The first group was based in Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Surry Hills, but they were on call to any of Sydney’s inner-city hospitals. Experienced administrators were also needed to handle requests, appointments and transport. Many health professionals had never worked with interpreters, so there was training needed there too, often by the interpreters themselves.

Demand for HC interpreters grew quickly, but they were also being asked to undertake written translations for hospitals – important documents like take-home notices to patients on what to do following a head injury, warnings to pregnant women not to have x-rays, or instructions on post-operative procedures.

Apart from not having enough time to take on more work, HC interpreters were not trained or accredited in translation. In 1980, government funding enabled the Health Department to set up a translation service to provide written health information for non-English speakers, and I was fortunate to be appointed the first coordinator of the Health Translation Service – the HTS. By then NAATI was offering accreditation tests in translation and I obtained translation accreditation – Italian to English – myself. Setting up small teams of freelance translators in priority languages, I decided on a policy of only appointing translators accredited at the first professional level, NAATI Level III. Together with my colleague Ursula Potter we developed a two-stage checking system, with two translators working on each publication. Accredited translators would work as either translator or checker on the translated version of a text, and they had to collaborate on the final version for publication.

Over 15 years the HTS provided health publications in up to 20 languages, and it won a Reader-Friendly award in 1993 for one of its publications. It was closed in 1985 and I took a redundancy. My next job was with the New South Wales Multicultural Health Communication Service, in production of multilingual health information online and guidelines for translation and on pre-translation editing.

Other career highlights for me were:

• joining you and Ezio Scimone as students in a master’s degree in Italian at Sydney University in 1989

• lecturing part time at Macquarie University in a postgraduate degree program on community-based interpreting, set up by Helen Slatyer in 2005

• presenting on interpreting and translation at Critical Link, triennial international conferences on interpreting in legal, health and social service settings, held in Canada and Sweden. We were both involved when AUSIT hosted Critical Link 5, in Sydney in 2007

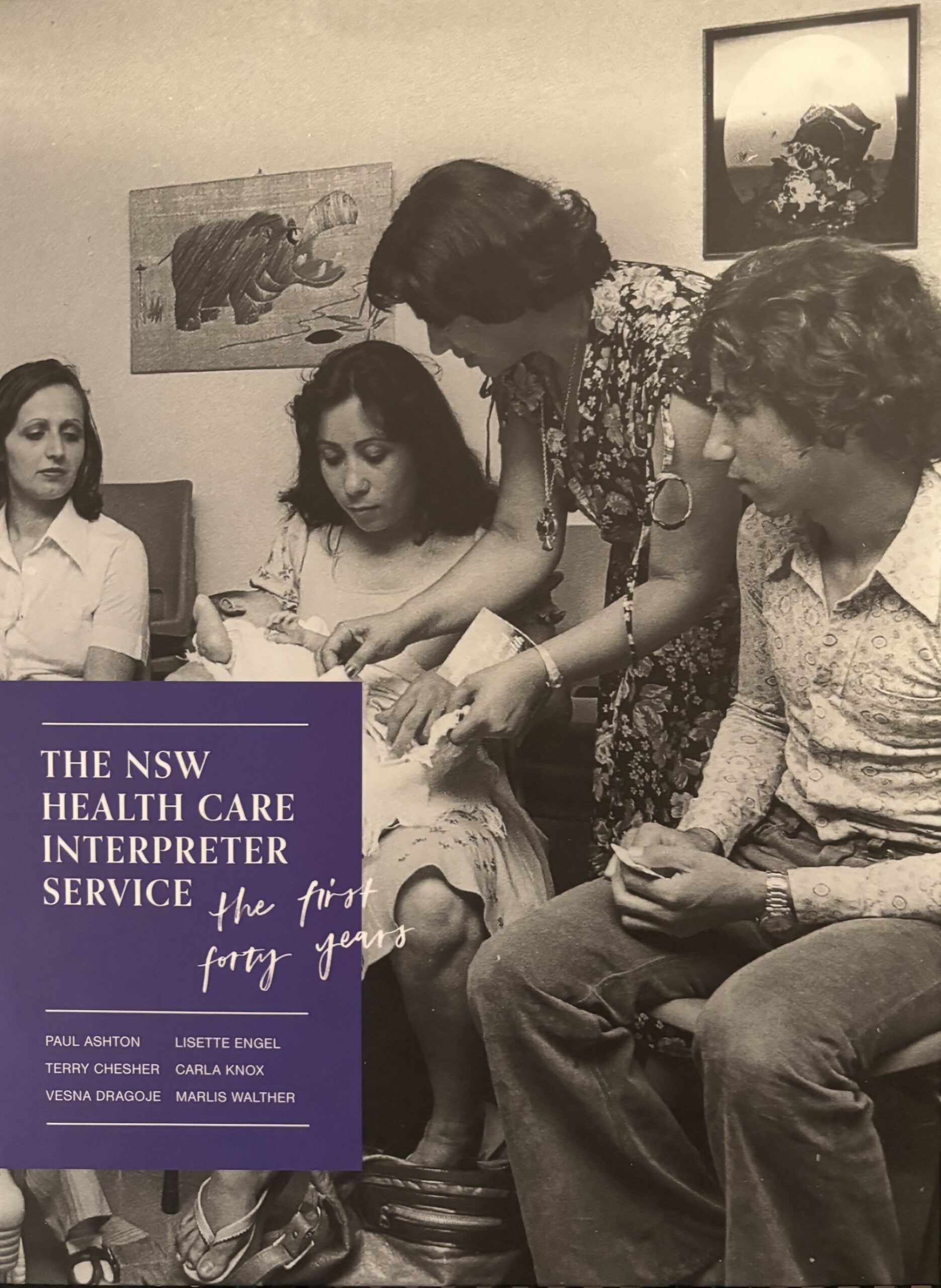

• co-writing a book – The NSW Health Care Interpreter Service: the first forty years, published in 2017 by Sydney Local Health District – with Paul Ashton, Lisette Engel, Marlis Walter, Vesna Dragoje and Carla Knox.

Cover of The NSW Health Care Interpreter Service: the first forty years (2017)

Barbara: And what about your history in AUSIT?

Terry: Well, my history with AUSIT is from the beginning intertwined with yours! How can we forget our work together on New South Wales and national committees, countless submissions to NAATI and to government, collaboration on conferences, first local, then liaising with other AUSIT branches on national and international events.

I met my first interpreting and translation colleagues, including you and Rosemary Morgan, in ATIA [the Australian Translators and Interpreters Association], the New South Wales state association. I heard of a meeting NAATI was convening in Canberra with the aim of establishing a professional T&I association. I passed the information on to the Ethnic Affairs Commission, and Lou Ginori (subsequently the first AUSIT President) and Kate Johnson were sent to attend. This was the start of AUSIT. It was hoped that AUSIT would take over the testing of aspiring T/Is, but this never eventuated as NAATI’s role was consolidated.

Barbara: Tell us about the establishment of AUSIT as you experienced it.

Terry: I remember the excitement when the New South Wales Secretary Barbara Ulmer and others organised the first national meeting of AUSIT at the Sydney Opera House. From then on state and territory branches formed committees and held their own branch meetings and AGMs, and representatives attended national AGMs and some other meetings.

Barbara: I remember our quarterly meetings were held via phone hook-up, requiring a fair bit of technical expertise and organisation to set up. We exchanged agendas and minutes by fax.

I was a founding member of AUSIT in 1977 and was made a Fellow in 1987, working on the New South Wales Branch Committee for many years and getting to know colleagues in other branches. Significant national milestones that I remember were the publication of the AUSIT Code of Ethics, and of an AUSIT policy paper that we co-wrote, Invisible Interpreters and Transparent Translators.

You and I were also involved with the AUSIT newsletters and the journal Antipodes, and represented AUSIT on SOCOG, the planning committee for the Sydney Olympics in 2000.

AUSIT hosted the FIT [International Federation of Translators] World Congress in Melbourne in 1996, and was invited to form a FIT sub-committee on community-based interpreting. Together with Helen Slatyer, Vadim Doubine, Lia Jaric and Rosy Lazzari we conducted an international survey of community interpreters, and I presented the results to the next FIT World Congress, in Mons, Belgium in 1999.

Barbara, you will remember working together on countless submissions to NAATI and to government on AUSIT’s behalf. AUSIT members also worked with legal professionals like the New South Wales Law Society on developing their guide to best practice for lawyers working with interpreters, as well as professional development courses for barristers. We also developed an annual program of AUSIT professional development events.

Barbara: Indeed, PD has steadily expanded to become a core AUSIT activity that provides members with a large and varied range of internal and external offerings.

Terry, thank you for taking us on this historical journey. Hopefully it will provide some interesting background for our newer members, as well as a few insights into how AUSIT’s past contributed to shaping its present.

Editors: On behalf of our readers, thank you again Terry – and Barbara!

Advertisement: