SPECIAL FEATURE: LITERARY TRANSLATION, PART 2

Uruguayan-born author, editor and English-to-Spanish translator Rosario Lázaro Igoa was intrigued to be asked to translate a novel that has Māori words and phrases scattered throughout the English. She tells us about the experience here.

‘I joined the action as the English-to-Spanish translator … who will live in the text for several months …’

I welcomed the unexpected opportunity to facilitate the metaphoric journey being taken by Auē, a Māori novel, across the southern Pacific Ocean right now, from Australasia to South America.

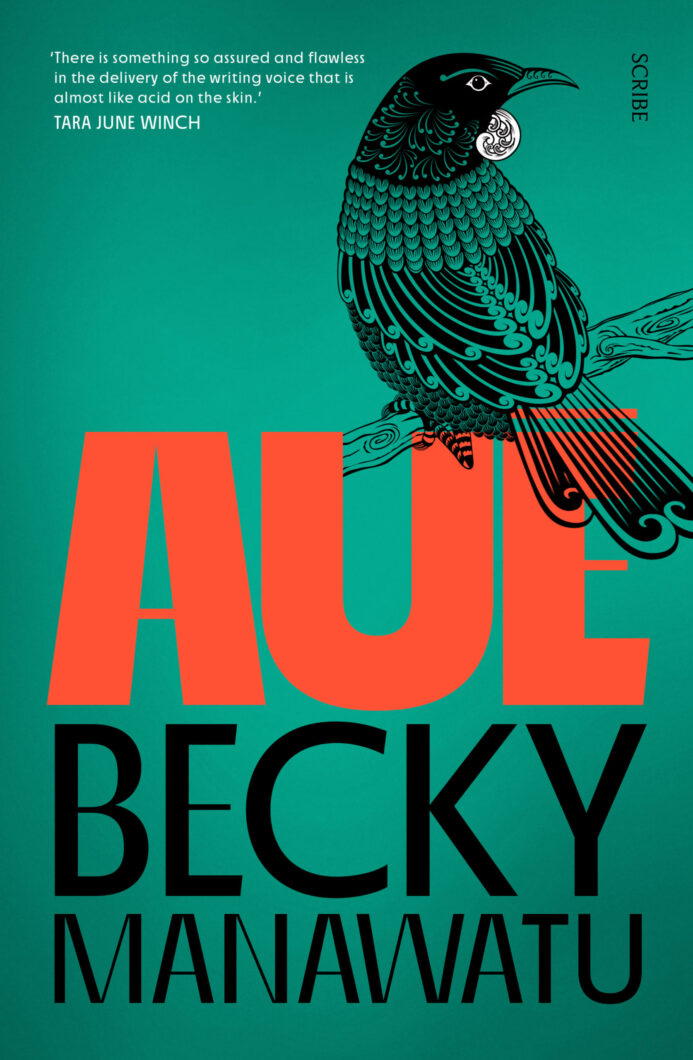

The first destination of this acclaimed, raw and heart-breaking book by New Zealander Becky Manawatu, written in English with an extensive use of Māori terms? Uruguay, a peripheral Spanish-speaking market of the Hispanic publishing industry.

Even though Auē is a text deeply linked to the Māori roots of its author, it is also becoming something else at the moment. Within a few months, when launched by Forastera (a publishing house specialising in translated literature), it will also condense a fresh approach to New Zealand stories that transcend linguistic and national borders.

As translators know, novels do not simply ‘travel’ by themselves. In his 1998 book Method in Translation History, Anthony Pym insists on the ‘material body’ of the translator being taken into account. In the journey undertaken by Auē, I joined the action as the English-to-Spanish translator – that is, when talking about a work of over 300 pages, an individual who will live in the text for several months (a place where the author already spent an even longer period).

Funding from Creative New Zealand’s Translation Grant Scheme, which supports the translation of NZ literary works overseas, allowed me to devote this extensive amount of time to the project. The grant – allocation of which was based on a translation of the first pages of the novel – is certainly playing a part in dynamising an unusual flux of literature, one that is free of interference from the traditional English/UK-centred mechanisms of criticism and consecration.

Every textual mediation has challenges, no matter how intricate or transparent the language might seem at first. Book translation, as a rewriting of every word over a lengthy period of time, seems to enable the closest of readings. From my own experience – as an author, an editor and a translator – there are countless traits of an author’s writing that only their translator gets to apprehend, and hence disentangle when rephrasing their words into a new language. I would like to focus here on the inherent and puzzling effect Māori words have in the English original of this novel, and how we dealt with this in the Spanish translation project.

Māori words are to be found throughout Auē’s English edition, with no footnotes, italics or further explanations on the pages themselves. There is, however, a complete glossary of the Māori words used at the end of the book – an invitation to the curious, but not an imposition (you might not even realise it’s there until you get to the final pages).

From what the translation process enabled me to observe, te reo (the Māori language) comes into action whenever the pākehā language (English) seems not to be enough for what a character needs to express. There is a certain alienation, combined with a dose of nostalgia for the (in some instances mythical) past, that makes them turn to te reo.

As we accompany the character Aunt Kat in a struggle to remember, te reo words surface in small actions and remembrances of family events, and there are also longer sentences, such as in Nanny’s dialogue with her grandsons. While her adult grandson Taukiri is dismissive of her stories, his eight-year-old brother Ārama feels the fascination of a language that carries a conflicted and emotional legacy in itself.

As a result of this critical reading of the text, the title remains unchanged in the Spanish translation (unlike the French, titled Bones Bay after a key location in the novel). Auē means a cry or howl, and is also used as an interjection of astonishment or distress. Given certain similarities between Spanish and Māori phonetics, I presume the word will be pronounced in an analogous way by Spanish readers. However, the strangeness is reinforced: not only does it refer to anything in particular (as it might for a New Zealander who speaks – or knows some – te reo), but there is also a diacritical mark – a bar on top of the ‘e’, indicating extra length and called a tohutō in te reo or a ‘macron’ in English – which doesn’t exist in Spanish. Readers of the translation aren’t expected to be able to read the tohutō – in fact, the intention is to expose them to the foreignness, yet familiarity too, of the text and the story.

As in the original, the translation has no footnotes or italics for Māori words, just a translation of the glossary. The Māori in the text is not an exotic trait, but the language spoken daily by Manawatu’s endearing characters, and therefore a constitutive part of their search for identity. In the translation I attempt to give floor to the conflictive historical link between Māori and pākehā: to resignify – but not simplify – the tension already existent in the original, in a different language.

The translation is also an invitation to Spanish-speaking readers to get a glimpse of a reality mostly unknown to them, that of contemporary New Zealand and its thriving literature. And since slang flourishes throughout the pages, a very distinctive Rioplatense Spanish* has been used throughout. Shuffling cards, I could discuss this in another article …

For those who haven’t yet read Auē, the original is available in Australia thanks to Scribe Publications; and in case you’re still deciding whether to read it, there’s a very positive review here.

* Rioplatense Spanish, also known as River Plate or Argentine Spanish, is a dialect of Spanish spoken mainly in and around the Rio de la Plata Basin, which straddles the border between Argentina and Uruguay.

Auē (original English version) cover reproduced courtesy of Scribe Publications

Auē (Spanish version, soon to be released) cover reproduced courtesy of Forastera

(designed by Camila Ugarte)

Rosario Lázaro Igoa is a writer, literary translator and translation studies scholar currently based in Sydney. She holds a PhD in translation studies (UFSC, Brazil), is a member of the National Researchers System (SNI, Uruguay), and currently researches with a group called Literary Translation History in Uruguay. Rosario has edited and translated Brazilian modernist Mário de Andrade´s anthology Crónicas de melancolía eufórica (2016) and translated many other Portuguese and English works into Spanish, and has also written three published works of fiction. You can read more about Rosario here.