To continue our series of interviews with AUSIT members who have contributed to the organisation and/or the T&I profession in Australia over many years, foundation member Dr Adolfo Gentile is interviewed by Professor Ludmila Stern.

… like many other children of migrants – I became the interpreter at home.

Adolfo has played a part in the development of T&I in Australia through a variety of roles and organisations.

Ludmila: Adolfo good morning! It gives me great pleasure to interview you for In Touch magazine. I think it’s correct to say that you are one of the founding fathers of the translating and interpreting profession in Australia, and you’ve had a very rich career with your involvement in AUSIT, NAATI other organisations. I’d like to talk to you about your professional life, but let’s start with your background. Where were you born? How old were you when you came to Australia, and where were you educated?

Adolfo: Well, I was born in Anacapri, a town on the Italian isle of Capri, and came to Australia with my mother and sisters in November 1962, when I was 12, to join my dad, who had migrated four years before.

In Italy I’d finished the second year of secondary school, but I didn’t know any English, so I was put in what was called Form 1, which is Year 7. So basically I started again, and did my whole secondary education in Australia.

After I finished school I got what was called a Commonwealth Scholarship, and enrolled at Melbourne University. I was going to do an engineering degree because I’d done all sciences, but at the last minute I changed my mind and enrolled in a languages degree with Italian and French. But in my second year my father became ill and I had to go to work, so I changed to studying part time and finished at the end of 1972.

Ludmila: What kind of work did you do? And what led you towards translation, what shaped your professional life?

Adolfo: Well, first of all – like many other children of migrants – I became the inevitable interpreter at home. I presume it took me three or four months to make myself understood in English, then I did what many children have done in this country – went with my mother to the doctor, and – you know – got involved in the administration of the household at a much younger age than a child in a monolingual household, dealing with the electricity bills, gas company and what have you, also more complicated issues like real estate, et cetera. But that wasn’t unusual, so it was just part of my existence, and I didn’t consider T&I as a career until much later.

Then when I was 17 – I don’t recall how – I was called to interpret at the Magistrates’ Court, and it was then that I realised that people who hadn’t the capacity in English were really disadvantaged , and shouldn’t be. This was still at the back of my mind when I had to go from full-time to part-time studies.

My choices were very pragmatic – I went into the public service because it was the only employer I knew of that provided four hours a week of study leave. I did general administrative work at the base grade until I graduated, and then I got an opportunity to join the staff at RMIT – not as a language person, but as somebody who had industrial experience in administrative training. They’d just started a graduate diploma in careers education and I was training people in different skills. I worked with a colleague who had experience in schools, and I had the workforce experience.

By coincidence, Dr George Strauss was on the interview panel. George was a French scholar who also had a long career working in T&I. He asked me to teach some French, then invited me to begin the first course in Italian interpreting at RMIT. For a couple of years I did a bit of each, then I moved to teaching interpreting fulltime.

At that time we also moved institution, first to what was called Prahran College of Advanced Education, then Victoria College, which became Deakin University. The long and the short of it is that the grants that originally funded the courses at RMIT ran out or weren’t renewed, so we had to find another organisation willing to finance them. It was a kind of community effort. At Victoria College we were actually incorporated fully into the teaching program.

Ludmila: And how did you become involved with AUSIT?

Adolfo: Well, when the program began at RMIT we were running two courses matching the NAATI levels, one at the Technical College and the other at the Advanced College. At that time, 1978, a good number of practitioners got together to form the Victorian Institute of Interpreters and Translators, a precursor body to AUSIT in Victoria. Analogous organisations were set up in most other states, and as you know, AUSIT was formed in 1987.

Since the birth of NAATI in 1977, it had been tasked with the creation of a professional body. It was like herding cats, if I can put it that way – even identifying who should be involved was a problem; when NAATI suggested we should have one national body, this threatened the power bases of certain people, so we spent years arguing. I can’t remember how many meetings I attended at the Victorian Institute of Interpreters and Translators to try and make the case that it was silly to keep these little splinter units all over the place (of course, Western Australia is still resisting to this day). So in about 1986, heads were knocked together and agreements reached, and NAATI moved to formally create AUSIT in 1987 in Canberra.

I was a member of AUSIT from the beginning and secretary of the Victorian Branch for a while, and in 1990 I went to the triennial congress of FIT in Belgrade with then National President Bob Filipovich, to present AUSIT as a candidate to join FIT. We were successful, and when AUSIT decided to put in a bid for the 1996 FIT Congress, I was asked to present the case at the Brighton Congress in 1993 – and again we were successful, beating Canada to the draw.

When I think back on it, this was quite an achievement for Australia, because most of the European institutions and courses dealing with T&I didn’t regard what we were doing here as professional. (Since ’84 I’d been running the department and all the professional level T&I courses in Victoria, and I went on a sabbatical to visit a number of institutions in Europe, but that’s another story altogether!) When the FIT Council voted to have the congress in Australia we said, ‘What have we done?!’ … but it turned out to be quite a success, and it was very beneficial – to the courses especially, and to the profession, because we actually saw that other people were doing similar things, and we could be proud of what we were doing, because up to then interpreting had been regarded as part of the welfare model, not as a standalone professional activity.

I became Chair of the Conference Organising Committee, so I was asked to join the FIT Council. I was on the Council for nine years: three as a member, three as Vice President, and three as President, from ’99 to 2002.

Was the FIT Congress in Australia successful? It’s probably best to ask other people, but from my point of view, yes. Even now, when I go to FIT events, people come up to me and recall it. I think it was partly because for many attendees – from Europe especially, but also America and Asia – it was the first time they had been to Australia and it was an eye opener in terms of what we were doing with T&I – it gave them a broader perspective.

Ludmila: Well, Adolfo, let’s move to the many years you spent as a member of the Migration and Refugee Review tribunals. Could you talk about that period of your career?

Adolfo:

Yes, I’d left Deakin University – voluntarily, but it was a bit acrimonious. I wasn’t going to accept any further cuts and allow them to still call the course a T&I program, so I resigned. I applied for a position on the Refugee Review Tribunal – which was later amalgamated with the Migration Review Tribunal, in 2005 if I’m not mistaken – and got it. So I was no longer a teacher of T&I, but a client. This produced some interesting situations, especially the faces on my ex-students when they walked in and saw me – so I made a point of talking to them, to allay any fears about me judging their interpreting. They weren’t interpreting Italian, the most common languages at the time were Turkish and Vietnamese, and later on Arabic, which we were teaching at the time at Deakin.

My work on the tribunals, with the pressures that exist in that kind of environment, helped me discern some of the things we could have done better in teaching. For example, I became a fierce advocate of briefing interpreters. I realised how important this is through the quite bizarre interpretations of the phrase ‘UN Refugee Convention’ I got at first – the Convention was often interpreted as some kind of conference.

The Tribunal already had a handbook for interpreters, but we revised it and I encouraged interpreters to read it before they came in, because it’s a fairly specialised area of law, and interpreting in this area – as with any interpreting really – is of utmost importance.

In ’97, when I was appointed to the Tribunal, I was Chair of NAATI (I chaired NAATI from ’95 to 2002), and also still involved in teaching, and I was on the FIT Council, and became its President in ’99. So I was fully involved, and I relayed the lessons I learned in my tribunal work to whoever wanted to listen, whether at FIT or within the profession.

Briefing is only obviously one aspect. Although we talk a lot about specialisations, I felt that wasn’t the main issue with the quality of the interpreting, it was more general preparation – general education and reading. If an interpreter came to the Tribunal, say, for a client speaking Tamil but knew little about either Tamil culture or Sri Lanka, I might get terrible interpretations when topography, geography or politics came up, because they just weren’t well enough prepared for the discussions we were having. It wasn’t a matter of word transfer. So that confirmed something in my own mind about our teaching, because when we started the bachelor’s degree we devoted a substantial amount of the course to general development of knowledge.

In the community interpreting sphere, most interpreters are of the same culture as the non-English language. So you would expect their cultural knowledge to be – if not adequate – at least better than the person on the street, but in certain cases it isn’t, for a variety of reasons. For example, the interpreter may have left the place when they were little and spent years somewhere else as an asylum seeker.

Ludmila: So when you were on the tribunals, were you – consciously or subconsciously – monitoring the interpreters? Or was the focus on what you were doing as a member?

Adolfo: My focus was on my role as a member, but subconsciously I was looking at what was going on, and some episodes were so glaringly deplorable they drove issues home to me, and I became a kind of unofficial ambassador and trainer of the tribunal members. Many members recognised that if they couldn’t communicate with the applicant there was no fairness, no justice. So they took this very seriously, and came to me if they had a question or an issue. As you know a considerable number of court cases have been overturned due to lack of competence on the part of an interpreter. Although I don’t agree – and I say this now quite readily – with the conclusions some judges came to about the role of the interpreter. Within this sphere of influence and prerogative there were decisions that they made which were supported by logic, but they didn’t know the ins and outs of interpreting, and expected certain things that were not possible. I’m sure you of all people know that very well.

Ludmila: I do, yes. Adolfo, you mentioned being Chair of the NAATI Board, and you’ve returned to the Board relatively recently, so could you talk a little about your work with NAATI over the years and your return.

Adolfo: Well basically, I first got involved with NAATI when I started working on T&I courses at RMIT, because some of us were asked – through the COPQ [Committee on Overseas Professional Qualifications] – to provide what would become tests – drafts of drafts, if you know what I mean. Then when NAATI was looking to form language panels, I was on its Italian panel from the very beginning, myself and Romano Rubichi from Adelaide. For a number of years he and I ran the tests all over the country. Then I was asked to participate in the state panels, which at the time – you might recall – were tasked with testing. Then I was invited on the precursor of the Qualifications and Assessment Advisory Committee (QAAC) of NAATI. When I finished my period as Chair (which involved chairing the QAAC too) in ’02 I think I had a year off, but after that I was asked to go back as Chair of the QAAC, so I did. I stayed on until the QAAC was turned into the Technical Reference Advisory Committee (TRAC), which gave me the pleasure of working with you for a few years. Anyway, basically what I’m trying to say is that it seems like I’ve been there ever since 1978 in one role or another, and I went back because I was asked to.

… it seems like I’ve been [at NAATI] ever since 1978 in one role or another …

Ludmila: How does being on the NAATI Board now compare with the previous experience?

Adolfo: Well, it’s a totally different experience, as it should be. One would expect things to have improved, and they have, especially – I think I can say this without breaking any confidences – between the members and the Board. This makes it a lot more engaging and interesting, and also rewarding. I think the profession has changed a lot since then, in this country and elsewhere, for the better. There are still problems, of course, but in general it’s better. There are more people involved and they have much more nuanced views on what the profession is and what it could be, which I think is good.

Ludmila: Yes, it’s much more open to the community, isn’t it?

Adolfo: Yes, and I think technology has provided a lot of opportunities to talk about what we do. A lot of people see this as a negative but I don’t, I see it as a positive. That’s another topic for another day – it’s important that we don’t treat technology as an enemy, but engage with it for the better.

So, the Board – I find that its remit has, in a sense, expanded. We still deal with the same institutions and the same themes, but the characteristics of the profession have made it necessary for the Board to be more versatile, more flexible and, I think, better informed.

Ludmila: A few years ago you became a doctor of philosophy. What motivated you to do a PhD, and how did you choose your topic?

Adolfo: My longstanding involvement with NAATI often made me think about what happens to organisations and their cultures – why they invariably reinvent the wheel, you know, and in increasingly short cycles. People seem to forget what happened five years ago and do it all over again, then get the same problems again, without learning. I could see this even in my lived experience because I’d been around so long. And why did a country like Australia set up such a thing when it did? Why did it take the shape that it did, which was a world first? So this is why I chose NAATI as the topic for my PhD. I wanted to look at the organisation’s whole history, but my supervisors persuaded me that that was too large a project, so I restricted my focus to its inception and development as an institution – which was good, as it allowed me to go really to the heart of the questions I posed myself. The full title was: ‘A policy-focused examination of the establishment of the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters in Australia’.

And the first part of your question, why a PhD? I did it when I was semi-retired already, so it was mainly for my own personal satisfaction. In the early ’90s I’d started a master’s degree in applied linguistics, and after a year I was advised to upgrade to a PhD, but at the time I was head of school and involved with NAATI, with FIT and so on. I did try, but I couldn’t continue – I just didn’t have the time, even part time – which I kind of regret. So in 2012 I thought, ‘Well, it doesn’t matter that I don’t work in T&I any more, I’m going to do it.’

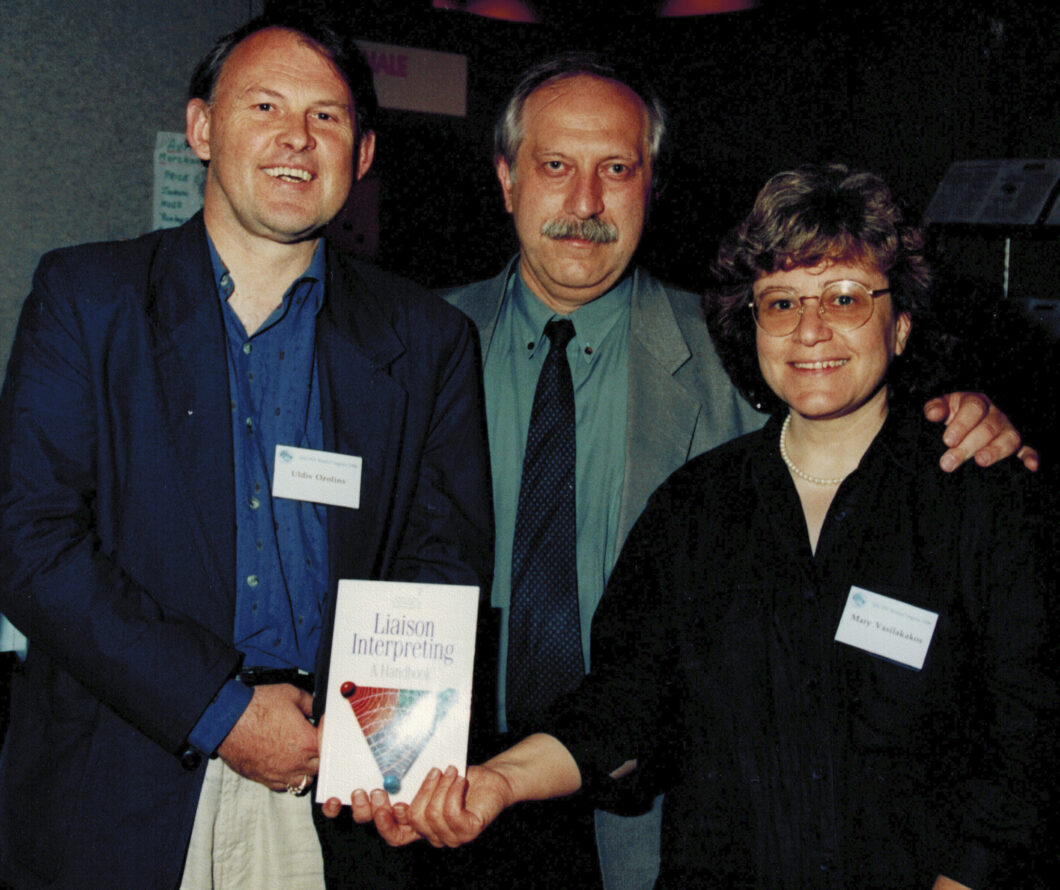

Adolfo (centre) with colleagues Uldis Ozolins (left) and Mary Vasilakakos, at the launch of their book Liaison interpreting: a handbook, published in 1996

Ludmila: Yes, and you must feel extremely proud, having achieved it.

Adolfo: Oh, yes, I do, on a personal and also on an institutional level.

Ludmila: My last question is: How has the multicultural and multilingual picture of Australia changed in the past decades, and how do you envisage its future?

Adolfo: Well, the multicultural and the multilingual ought to be kept separate, I think – although of course they’re related – because when I was working, multiculturalism meant a certain thing. But I think that particular view of the term has evaporated and it’s now basically a synonym for having many cultures living together, whereas then it was much more of a plank in the government’s policymaking. A lot of things that are happening now are still echoes of the original ’70s policy, but the reasons have turned more into instrumental ones, such as political or commercial reasons. We argue for diversity more on those parameters than we do on other – more ephemeral, if you like, but to me more important – parameters. I think that’s how it’s changed.

Also, there’s been an explosion in the number of languages spoken in Australia. There always were quite a number, but now we have even more – apart from the Indigenous languages, which deserve their own mention, and Auslan of course – both of which we included in the NAATI system in the mid-’80s.

At first there was some mirroring of languages on the basis of the migration program, and this is still there. But the program itself has abandoned all pretence of nation building, it’s going towards commercial achievements and productivity and industrial development and so on, so we’ve got a much broader range of people coming from a much broader range of areas … just the people from the Indian subcontinent brought in seven, eight or nine different languages. So this is what I think has happened. Anyway, that’s my own take on it. Obviously it’s a political view as well, because the policies of government have moved forward without fixing the fundamental problems. We still have to find grants in order to be able to test and run courses in Indigenous languages, for example, we don’t have an institutionalised approach, and so on.

The fact that diversity is celebrated now is a big improvement, and I think that will continue, even though sometimes it’s a bit tokenistic – for example, advertisements on television have compulsory diversity now, but it’s sometimes very stilted and unhelpful … but at least we’re recognising and talking about it, and it’s becoming more mainstream, and this is a more mature response than in the past.

And in Australia the quantum of people who are born overseas, or with parents born overseas has increased. I don’t know whether I should even go here, but I will – when I was growing up there was a kind of hegemonic assumption about Anglo-Saxon culture which led to, for example, someone telling me and my mother not to speak Italian on the tram. This attitude is dissipating, we’re not over it quite yet but we’re in a different place, and in my view we’ve got to deal with – not deal with, treasure – what we’ve got.

Ludmila: Yes. Adolfo, thank you so much for sharing your very rich life, professional experience and numerous achievements, but also for your analysis and reflection. I’m sure our readers will enjoy this interview very much and learn a lot from it, so thank you again for so much of your time.

Adolfo: Not at all, not at all.