INTERVIEW SERIES

Interviewed by Sophia Ra

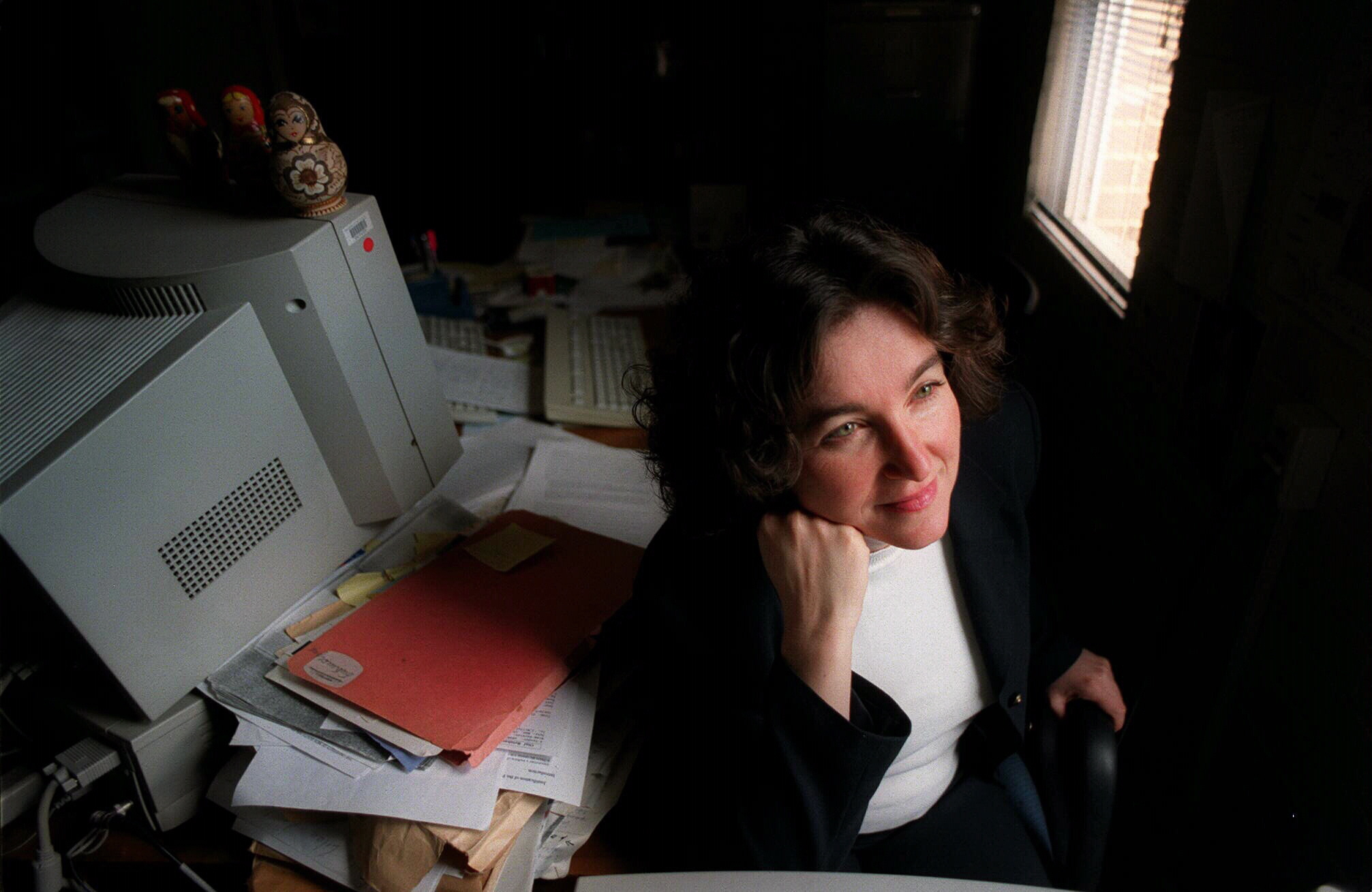

For the third in our series of interviews with long-standing AUSIT members who have contributed to the organisation and/or the T&I profession in Australia over many years, In Touch Editorial Committee member Sophia Ra interviews Professor Ludmila Stern.

So I thought, ‘I’ll sit at home with my baby … and do translation.’

Professor Ludmila Stern founded the Master of T&I program at UNSW, where Sophia now tutors, having completed her PhD there in early 2022.

Sophia: Ludmila, thank you for your time today.

Ludmila: It’s my pleasure! Thank you for inviting me.

Sophia: It’s funny … I’ve known you a long time, but I’ve never asked you about your career path, how you started as an interpreter, so when I heard about these interviews, I thought it would be really interesting to interview you.

Ludmila: So would you like me to answer questions, or just speak in a free narrative?

Sophia: I’ve prepared some questions, but maybe you can start by telling me about your early life?

Ludmila: OK, so, I was born in Moscow, which was the Soviet Union in those days. I’m actually a first generation Russian because my maternal grandparents – who were Communists before the Second World War – migrated from France to the USSR for political reasons. They were Polish Jews, but they’d studied medicine in France – both were medical doctors – and having joined the Communist Party, they moved to the Soviet Union in 1935 or ’36, when my mother was a little girl. So it’s thanks to them that I learned French – French is my first foreign language. Russian, understandably, is my native tongue, my first language.

So, French was spoken by my grandparents in the family, but I also studied it formally at the university. My English comes from high school, but it wasn’t a very interactive English – it was really meant for reading and writing, and when I came to Australia in 1979, I discovered that English is nothing like what I’d been studying for years in the Soviet Union. So, I would say my main languages are still: Russian first, English second now – or they are somewhere on par – and French is my third language now.

As I said, I studied languages both informally, but also formally. I’d started a tertiary degree in the Soviet Union, in French and German, and when I came to Australia in 1979 I enrolled at the University of New South Wales (where I’ve now been teaching all my adult life!) to study Russian and French literature and language, and (briefly) German; and my first degree was a double honours degree in French and Russian, completed with first class honours.

Sophia: So, how did the interpreting come in?

Ludmila: My late mother-in-law, Gerda Stern, was a Polish interpreter, and she’s the one who encouraged me – while I was still at university – to try my natural skills at interpreting. Actually, initially, she said ‘translation’. You know, in Russian we have one word for both translation and interpreting, so I understood it as translation.

So I thought, ‘I’ll sit at home with my baby – who was just born – and do translation.’ She started taking me to various agencies and introducing me. She took me to what was then the Ethnic Affairs Commission (nowadays it’s Multicultural New South Wales), and I did some tests there – I had to do quite a challenging dialogue and speech interpreting test that they administered themselves, and I also started sitting for various NAATI exams.

So, this was my introduction to the field, and I discovered there was more demand for interpreting than translation. Today it will sound probably totally outrageous, but there I was, untrained, unbriefed, had no idea what was going on, and I was sent to a medical interview, and then to a legal consultation, and I had nothing except the address where it was taking place. I don’t know what I was doing – probably I was interpreting, and somehow I knew that I had to interpret in the first person. But that was in the days before the AUSIT Code of Ethics was developed, so I had no idea about professional conduct.

And like many interpreters in those days who were bilingual, who were untrained, not briefed by anyone, not mentored, I kind of just drifted. I probably learned quite a lot from my mother-in-law and her experience as a Polish interpreter in different settings, including in court, but she was also untrained. So our conduct was pretty much intuitive rather than informed by the Code of Ethics or other guidelines.

Eventually I started working in courts as well, and then more things happened … I started working as a conference interpreter too, and as a subtitler at SBS. Hmm. Yeah, and my academic career started in 1989, and from then on I tried to combine both, so interpreting became also part of my research.

Ludmila (right) interpreted for the late Soviet documentary filmmaker Marina Goldovskaya (left) during the Sydney Film Festival 1989, which included Goldovskaya’s 1988 film The Power of Solovki.

Sophia: That’s all really interesting. I never knew you had this background, with full-on language influences by your grandparents and your mother-in-law … So English wasn’t your focus when you were in Moscow.

Ludmila: No, no.

Sophia: It’s similar in Korea – we learn writing and reading, but not really communication.

Ludmila: Exactly, exactly.

Sophia: Can I ask why you came to Australia?

Ludmila: Well, coming from a family of political migrants who were terribly disappointed in the Soviet system, and who suffered under it – you know, my grandfather was one of the many victims of Stalin’s repressions, he was arrested in 1937, but eventually released – my family were … maybe not full-blown dissidents, but there was a spirit of disapproval of the system. It was very clear that my family disapproved of the Soviet regime and its ideology and policies.

Another reason was the state’s antisemitism – as a Jew I had limited opportunities in the Soviet Union. So this combination of reasons eventually led me to migrating and finding myself in Australia.

Although my in-laws were Polish migrants, my husband is Australian born and the family spoke English at home. At first we lived with them. So clearly I had to start speaking English pretty much straight away, and then I was studying at the university. I was also teaching Russian at Moriah College, which is a Jewish high school. That’s how English became my working language, and with time it replaced French.

Sophia: So you started working as an interpreter back then without any NAATI accreditation …

Ludmila: … but I soon got NAATI accreditation. Around 1985 to ’87 I passed what was known as Level 3 Russian-to-English and English-to-Russian translation (both directions), and later on Level 3 interpreting, which allowed me to interpret in court – until then I could interpret in health care settings, in legal non-court … My current certification as a conference interpreter into Russian came many years later.

Sophia: And it was before the Code of Ethics?

Ludmila: Yes, if I’m not mistaken, the AUSIT Code of Ethics was written in 1995 …

Sophia: All right, so you worked with Multicultural NSW and other agencies … how did you come to focus on legal interpreting?

Ludmila: I think the turning point was in the mid/late 1980s, early ’90s, when I was employed as a Russian translator and interpreter by the Commonwealth Attorney General’s Department, in an organisation called – cryptically – a ‘Special Investigations Unit’. The unit was conducting investigations to support the Australian War Crimes Prosecutions. They were prosecuting alleged perpetrators of Nazi crimes on the territory of the former Soviet Union during the Second World War, so they needed interpreters in Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, Croatian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Yiddish, German of course …

I translated witness statements. I also travelled to the Soviet Union to interview witnesses and participate in official negotiations with the then Soviet Prosecutor General’s office and other officials. That was my official role.

When the proceedings began, in South Australia in 1990 or ’91, it was clear that something was going very wrong during the actual hearings. Communication with the witnesses, who were brought from the USSR mainly, wasn’t going well: there was a sense that witnesses and lawyers spoke at cross purposes. These were supposed to be very persuasive witnesses who’d been very cooperative during the investigation stage, but once they found themselves in the Australian court, suddenly they were uncooperative, they were contradicting themselves. They were obviously very unhappy with the way they were interviewed and cross-examined in court, there was a sense that these carefully constructed cases were falling apart.

So the DPP of South Australia asked me to analyse the court transcripts and try to understand what had gone wrong … Why had these witnesses suddenly become so uncooperative and lost their credibility? Why were they giving such odd responses? … so I started looking at the English transcripts again.

In those days they didn’t record the original, so I couldn’t actually compare the transcripts with the Russian or Ukrainian originals to check their accuracy, but it was obvious that something was going seriously wrong. There were some instances of misinterpretation, but not significant inaccuracy of content. What was very interesting was that clearly the witnesses often didn’t understand the strategic intention of the questions, whether it was because the questions were interpreted very literally, or the witnesses couldn’t understand the intention, because they came from a very different legal system, a very different cultural background – they were mostly rural witnesses – so they could not respond to the questions, even those that were asked by the prosecution (they were all witnesses for the prosecution).

I was asked to analyse the transcript and write a report on the causes of miscommunication between the lawyers and the Russian- and Ukrainian-speaking witnesses, and I think that’s what really triggered my research into court interpreting, you know.

So, what had gone wrong? Was it that the interpreters were unsuitable, or untrained, or incompetent? Or was it something else? Was it also that the two sides followed what’s called different cultural scripts, whereby they didn’t quite know what the other party was talking about, and as a result of that witnesses’ responses and demeanour were misinterpreted … their level of intelligence, their reliability as witnesses were misinterpreted, you know …

Since then there have been studies about this, including one about bilingual courtrooms by Susan Berk-Seligson, about Aboriginal witnesses and the law by Diana Eades, and others about the lack of equivalence between different vocabularies and systems, by the Polish–Australian linguist Anna Wierzbicka.

Later on I went to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, where my colleagues from the Australian War Crimes Prosecutions Unit were now working – and I started investigating interpreting in international courts and tribunals, trying to understand the secrets of their success, and comparing interpreting practices at the international courts with those at domestic ones. So that’s what really triggered my interest in court interpreting as a research area.

Sophia: That’s really interesting, it’s not just translation – because you didn’t have the original speech there was nothing to compare, so you put on a different hat and analysed the transcripts … analysed, sort of, between the lines.

Ludmila: Correct, I just tried to figure out what could have could have been said in the original – why such and such a response was given. Yeah.

Sophia: Hmm. So, you had all these experiences as an interpreter and translator, then moved on to your research, especially in court interpreting, then became an educator at university. Right?

Ludmila: Actually, I have to step back, because initially, I was employed in the Russian Department at UNSW. My PhD had nothing to do with T&I, it was more in cultural history … cultural diplomacy of the Stalinist Soviet Union. My PhD and publications were about how the Soviet Union influenced Western intelligentsia – writers, journalists, scientists and so on. That’s where I started, but because I kept working as an interpreter, I was also researching in the field of interpreting.

So for the first 15 or 16 years at UNSW I was teaching Russian and Russian Studies, and researching literary and historical topics of French–Soviet or Soviet–Western interaction, but I kept working as a T/I … for example, in SBS’s subtitling unit, and as an interpreter during the Sydney Olympics in 2000 … and as I was combining both, I thought it would be a good idea to found a program to help students of language studies pursue a profession. Until then UNSW didn’t have any T&I subjects.

So, in the first instance, I introduced an interpreting subject at undergraduate level with different languages, and it was successful … I could see that students of languages were really interested in exploring what interpreting is like. We had French, Russian, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, Chinese and Indonesian, that was the start. Then in 2005 I suggested to the University that we develop our own graduate program in T&I, partly because of student demand. Students were saying, you know, ‘Why do we have to go to another university? Why can’t we continue here?’ So I explored how other universities, nationally and internationally, offer T&I, and with the blessing of the faculty, I developed and introduced a master’s program in T&I.

Initially, I was the only staff member, and also the convener. We had language tutors, and gradually the program grew, the student numbers grew, and so we created new positions, and Mira Kim joined us … I think, before that Sean Cheng did … then we invited Sandra Hale to come from Western Sydney University. So that’s how the program developed. We didn’t expect that we’d mostly have international students!

Sophia: Hmm, okay, I knew you were a founding member of UNSW’s Master of T&I program, but I didn’t know all these stories.

Ludmila: Yeah, that’s right. So, for a few years I was the only one, teaching all the courses alone, and we had tutors who were T&I practitioners, and it’s only later, 2009, 2010, I think Sandra came in 2011, and that’s when we really built up this – you know – lovely team of colleagues.

Sophia: So then, you were wearing all these different hats: interpreter, translator, educator …

Ludmila: Too many hats!

Sophia: But I think it’s good, because you can connect everything: practice, research, training, everything, so you can see the links, right?

Ludmila: Yes, that’s right.

Sophia: And you witness your students actually becoming interpreter practitioners, working actively and going back to the community and even volunteering for AUSIT, now!

Ludmila: Absolutely. They’re working in domestic and international settings. Definitely.

Sophia: Ludmila, you’re a really good narrator, you’ve answered all my questions before I asked them! I have two more: when did you join AUSIT, and what have you done as a member?

Ludmila: Look, I don’t remember when … in my mind I’ve always been a member! You might be able to check and refresh my memory. But again, I joined because I was encouraged by my late mother-in-law, who felt that a professional association was a good thing, a useful thing.

Sophia: Yes. Was your mother-in-law an AUSIT member too?

Ludmila: She was, yes, yes.

I wasn’t a very active member at the beginning, but I met lovely enthusiastic people at AUSIT events … people like Barbara McGilvray and Terry Chesher, and other great colleagues. And I did give a few presentations based on my research into international courts and tribunals and working conditions there, a long time ago. In the past couple of years I’ve given a few presentations, too, about the Recommended National Standards for Working with Interpreters in Courts and Tribunals (RNS), and the responsibilities of judicial officers.

I’m also involved with the regular research seminars we run at UNSW, which are open to all AUSIT members, with NAATI certification points for attendance; and in 2021 In Touch published my interview of two colleagues, Cintia Lee and Sylvia Martinez, about their successful advocacy around working conditions for court interpreters.

Then last year, together with Despina – who was then a Vice President of AUSIT – we represented AUSIT at the FIT Congress in Cuba, and gave presentations. That was a very memorable event, and since then I was successfully nominated to the Fit Standing Committee for Legal Translation. One activity I’ve initiated and am leading is adapting the RNS to legal systems in other countries that have associations and are FIT members – so hopefully something good will come of it, and Australia will again be an international leader in the T&I industry.

Sophia: Well, we’ve covered so much in this interview! – so thank you very much again.

Ludmila: It’s my pleasure, Sophia. I hope AUSIT continues going from strength to strength. It’s been very fortunate with its recent and current presidents and committees, and so many volunteers giving their time to improve the professional lives of translators and interpreters with interesting, valuable PD sessions and other events.