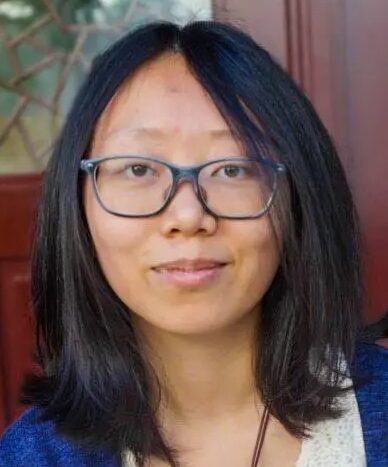

Our October issue covered literary translator Yilin Wang’s recent battle with the British Museum, which had published her translations without her knowledge or permission. To find out more about Yilin and her work – which ranges across translation, writing and editing – In Touch’s Editorial Committee members Sophia Ra and Cristina Savin put together some questions, which Sophia then put to Yilin via Zoom.

‘… I witnessed some racism: a bookseller used slurs to describe a Chinese poet reading in Mandarin …’

Sophia:

Yilin thank you very much for your time today, it’s a great pleasure and honour for me to interview you. In the last issue of In Touch we examined your recent battle with the British Museum and settlement with them. Today, I’d like to focus on you and your work. So before we move on to your work, can you please tell us a bit about how and when your interest in translation or in language originated?

Yilin:

I came to translation with a creative writing background. I’d been writing original works of fiction, poetry and nonfiction for over ten years, and became increasingly interested in non-Western, non-European literary traditions – especially Sinophone literature, being someone who is bilingual in Mandarin – as a source of inspiration. I wanted to open myself up by reading works that embrace a wider range of storytelling, and different ways of using language and of experimenting with writing and genre and form. While doing my MFA (Master of Fine Arts) in creative writing, I started to experiment with translation in this context. I took a multi-genre writing workshop for which you could submit original work in any form or media, or translations, and I submitted some of my translations of Classical Chinese poetry.

This was also around the time when Sinophone speculative fiction was becoming very well known in North America, winning awards and so on. It was part of a wider trend of East Asian dramas and science fiction, fantasy and comics becoming very popular here, and I started meeting other writers who had crossed over to translation, so that was a part of it too.

And during my MFA, which I did in Canada, I witnessed some racism: a bookseller used slurs to describe a Chinese poet reading in Mandarin and was very disrespectful. I started thinking a lot about how the Canadian publishing industry isn’t very welcoming towards people of colour – all the gatekeeping, especially towards people writing in other languages. So, all these different factors contributed to me wanting to pick up translation and try to bring more translated works into English.

Sophia:

It’s interesting that you were a writer first, then you became a translator. I’m wondering if there’s any intersection or influence between these different disciplines?

Yilin:

Definitely. Yeah. To be a literary translator, you generally need to be a very strong writer in the language that you’re translating into. So even though I’m doing literary translation, it feels to me like a form of creative writing, because I’m reading works written in Mandarin and then (re)writing them in English. So for me it’s very similar, but obviously you’re working within many constraints, that’s the one difference, and it forces you to be very creative. So doing literary translation has trained me to read in a more careful way, different from what I do as a writer, and I now bring this skill back to my own writing.

And when I write in English, as someone who is Chinese Canadian, I write a lot about diaspora experiences and about my relationship with language. I’m often dealing with materials that require a lot of cultural context and sensitivity – so even before I’d done literary translation I was practising the skills a translator uses: I had to explain, I had to think about how to bring certain concepts or terminology into English in my original work, I’ve always been thinking about that. Doing literary translation has made me think more about that, become more conscious of such decisions. And as I’m multilingual, it’s been very helpful for me to take that and apply it to how I think about my own writing.

And then editing … I’ve been an editor for different literary publications and journals, and I’ve also done some copyediting of translations for publishers, and given feedback as a sensitivity editor for translated works, or works featuring Chinese culture and characters.

My work as an acquiring editor for publications really overlaps with my literary translation work, because as a translator, especially for poetry, I’m often deciding for myself who I want to translate and picking the poems, then asking for permission, then translating them. I have to think like an editor in some ways, because I choose poetry that I think is well written, that I like, but also that I think would be suitable for publication in English when I send it out to a lit magazine or a book publisher. So I’m using that kind of editorial sense when I choose works.

And then, of course, as a copy editor and sensitivity editor, again, I use cultural knowledge – which I also use as a translator, thinking about how phrases are being rendered and looking at, perhaps, the use of Chinese language and how context is described.

Sophia:

So you work mainly from Mandarin to English?

Yilin:

That’s right.

Sophia:

To me translating into English is more challenging, as English is my second language. Do you see any difference between the two?

Yilin:

As a writer in English, I tend to have my own voice and style that I’m used to. I’ve experimented with different forms, but I have certain genres and aesthetics that I’m most comfortable with and that I can bring to my original writing. When I translate, I encounter writers who write in different styles and voices and registers, which pushes me out of my comfort zone. I find it kind of fun, but also difficult to translate their voices into English and work within the constraints of the source text.

And in Mandarin, for example, there are lots of idioms, like chengyu – four-character phrases that are very, very compact and have whole cultural stories embedded in them. These are very hard to render.

And with classical poetry, again, it’s very different from English, so I have to cross a big divide in terms of how different the languages are. And stylistically it can be quite challenging, because so much is left ambiguous and unsaid and it’s very compact, and the syntax is different and you have to interpret. Those are the things that I don’t encounter when I’m writing my original work. So in these ways, translation can be more challenging. And some of the poets I translate, including Qiu Jin, are not living authors, so it’s not like I can ask them questions – I’m just left with the poems to decipher.

Sophia:

That’s true, and as you mentioned, Korean, Chinese and some other Asian languages are kind of contextual – they don’t necessarily explicitly explain what is meant, but we sort of guess based on the background or context. So it’s probably a bit more tricky to deliver messages from those languages into English, which is more explicit, I think.

Yilin:

I agree. Yeah. I think there’s a lot that’s implied and left ambiguous, for readers to infer. But English is a language in which more information has to be made explicit – for example verb tense, or whether something is plural or singular.

Sophia:

Yeah, that’s true. So you translate from Mandarin into English, two very different languages and very different cultures as well. So focusing on poetry now, do you experience more constraints, limitations, or more freedom in recreating poems from Mandarin into English?

Yilin:

I do think of translation as a form of creative writing, creative art, so I do feel empowered when I translate poetry to take more risks and, kind of, be more free, and I think more about the effect that it creates rather than what’s literally on the page, word by word. So I do feel I have that freedom.

I do find it challenging with Classical Chinese poetry, because there are lots of formal qualities that don’t translate well into English. For example, the meter is based on tonal variation, because Mandarin is a tonal language, and English doesn’t have tones. And also, when you’re translating from the classical language, we don’t even know what the original poem sounded like, because Classical Chinese sounds quite different from modern Mandarin. Lines that are supposed to rhyme often don’t any more. So then what do you do with that when you translate it into English, which is even more different? That’s something I think about a lot.

And also the compactness and conciseness. Qiu Jin’s poetry was written in the period that was transitioning from the classical language to modern Chinese, so her poetry poses for me the specific challenge of navigating that linguistic shift. It’s rooted in a classical poetic form, but using more modern vocabulary and diction, and it’s kind of following the constraints but also kind of breaking them at the same time, so that has been one of the bigger challenges for me as a translator of poetry.

Sophia:

So are you able to translate Qiu Jin’s mix of the modern and traditional styles of poem into English?

Yilin:

I do try to do that. For example, when I translate Chinese poetry – in classical Chinese poetry, we have a lot of parallelism …

Sophia:

Yes, I know.

Yilin:

Is it similar in Korean?

Sophia:

When I was in high school we actually learned Chinese poems. They always have a few different lines with the same, sort of, rhyme [Sophia gestures with her hands, implying two things parallel] … that’s how I remember it.

Yilin:

… so you know there’s a parallelism with the imagery, and also with the rhythm and the syntax … a lot of things are in parallel. So when I translate Qiu Jin, I do try to preserve that kind of quality and bring it to my translation of her work because as a poet, I do care about these kinds of details, and I understand that they’re often intentionally done by the poets. Being a writer myself, I can put myself in the writer’s shoes and imagine why they made certain kinds of decisions, and I use that to guide me in thinking about what to prioritise when I translate.

So I don’t necessarily translate things like rhyme, which is more contrived and harder to render in English in a way that’s natural compared to the Mandarin. But I try to translate the larger stylistic features, for example, in terms of the parallelism or the general feeling of the classical poetry. And in terms of the modern aspects, depending on the poem, I do try to make the diction and the register feel a little more modern and colloquial at times, even in that classical form. That’s something I’m always trying to find the balance for, because it’s an older style, but at the same time, not as old as the ancient classics.

Sophia:

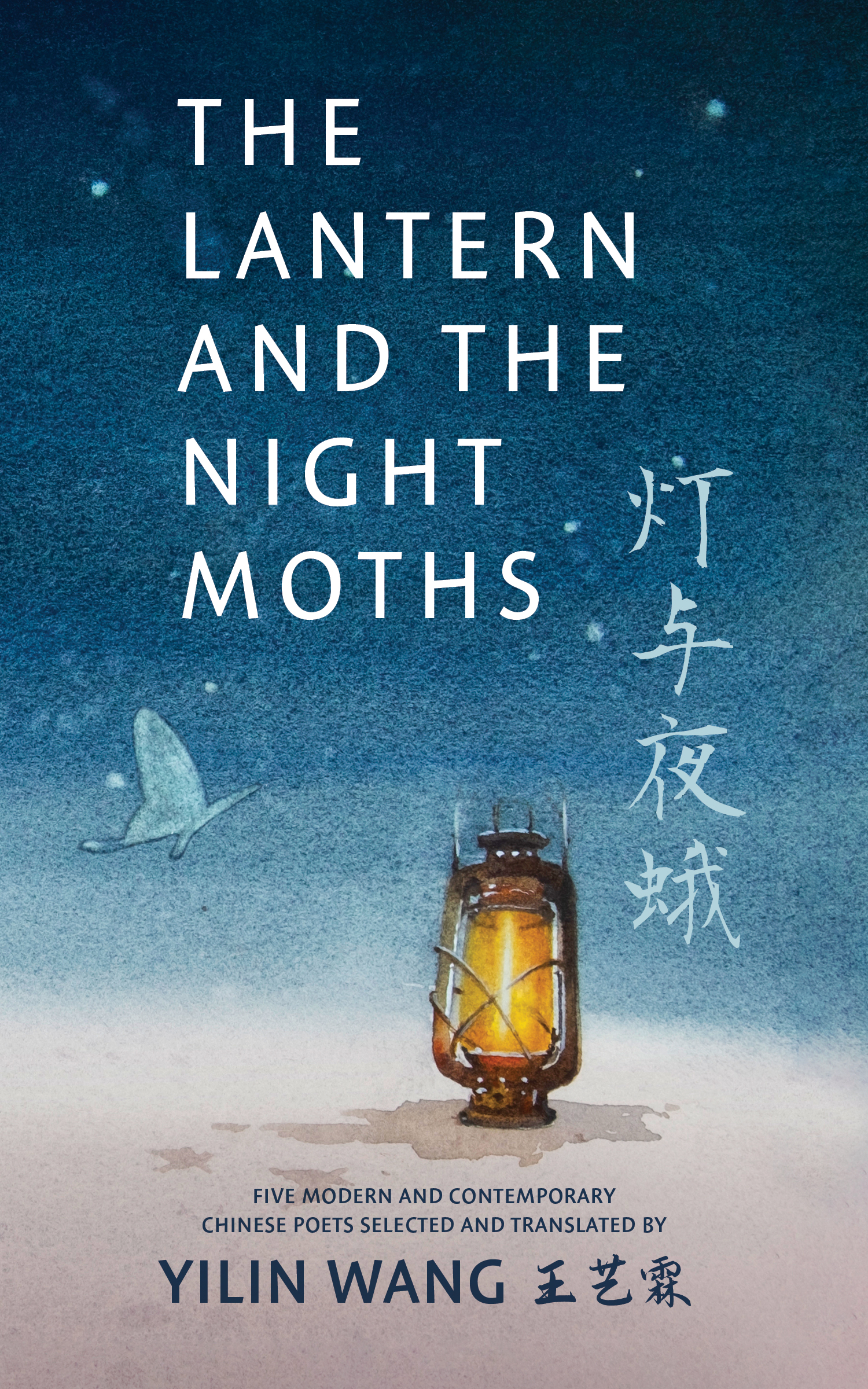

Fascinating, really interesting. I’ve never translated poetry. I keep comparing your work with my own. I usually do subtitling, and because there’s a time/space limit, I always have to be creative. So, moving on to your upcoming book The Lantern and the Night Moths, I think you’ve just finalised the editing?

Yilin:

I’ve submitted my final manuscript and we’re at the copyediting stage now and proofreading, and it’s being laid out as a book.

Sophia: And you’ve focused on some of China’s most innovative modern and contemporary poets – Fei Ming, Qiu Jin, Zhang Qiaohui (sorry about my pronunciation!), Xiao Xi and Dai Wangshu … I’m wondering why you chose these particular poets. Can you give our readers a glimpse into any of the poems or poets that you introduce?

Yilin: This project came about as a result of my work as a poetry translator over the last few years. Drawing on my skills as an editor, I read a lot of modern and contemporary poetry, and found poets whose works I feel are very innovative, unique and interesting, yet weren’t being widely read by Western poets and readers of poetry. Some are better known and have been translated in the past, especially Dai Wangshu, who is one of China’s most famous modern poets, but are mostly being read in academic circles.

So what I wanted to do was to bring my background as a poet and editor to translating these writers’ works, so that they can hopefully reach a more mainstream audience and be considered in context with Anglophone poetry – so people in the Chinese diaspora, and others who can’t read Mandarin but are interested in Chinese poetry, can access the works of some modern and contemporary poets from China.

A lot of people have heard of the Classical Chinese poets like Li Bai and Du Fu, but the modern and contemporary poets who were writing in their aftermath are less well known. So I think of my book as offering a selection of some very interesting voices from these times.

Qiu Jin, as folks may already know, was basically the first modern feminist poet from China, and is well known as a historical figure. But her work has mostly only been translated in an academic context, and I wanted to offer more creative translations of her work. And there are other contemporary poets, like Xiao Xi and Wangshu, whose works are unique but have never been translated before.

So there’s a range of different voices here, and for each poet I’ve included a short essay that reflects on what’s interesting or unique about their work, or what I was thinking about as a translator when I was translating it – reflecting on the translation process. Many of the essays have to do with the art, craft and skills of literary translation, and are rooted in my experience as a translator from the Chinese diaspora. I hope the book can serve as an introduction for folks interested in modern Sinophone poetry or in translation, or both.

Sophia:

So in this book you’re a translator and a writer at the same time?

Yilin:

That’s right.

Sophia:

I think what you’re doing is really important, letting other people access great works that are not written in English – poems in your case. I look forward to it.

So, that’s pretty much all my questions. Is there anything else you would like to tell us about, or anything that’s missing?

Yilin:

You asked really great questions. Thank you so much for putting this together. There are a couple more things I’d like to mention.

Have you heard of the Three Percent Problem?

Sophia:

No, I haven’t.

Yilin:

Okay. So the Three Percent Problem came out of a study done in North America. It describes the phenomenon that of the books published in the US every year, translations into English constitute only three percent. And this is all languages into English, and every kind of book – textbooks, nonfiction, instruction manuals … and within that, I think, 0.7 percent is literary translation. So the problem is: how do we increase this percentage? I’m sure that translations into Chinese published in Sinophone regions – and translations into Korean published in Korea, too – make up a higher percentage of the totals, so it’s not an equal exchange that’s happening.

Sophia:

Yes, that’s interesting.

Yilin:

Lastly, I want to talk briefly about another reason I was interested in translating Chinese poetry. I was noticing some unethical practices in its translation into English, which I think happen a lot with Asian poetry. Have you heard of ‘bridge translation’?

Sophia:

No.

Yilin:

So, in bridge translation, a writer in the target language who doesn’t speak the original language is asked – often by a translation organisation or publisher – to take a literal word-by-word rendering of a text and rewrite it. For example, for a twenty-character Classical Chinese poem they would first have a Mandarin speaker – maybe an actual translator – write down the definition of each of the characters in English. These would then be given to an English-speaking poet or writer who doesn’t know Classical Chinese, to write a poem based on the definitions. The result – which could be a very creative piece – is called a translation and credited to the English speaker, while the person who did the word-by-word translation is often sidelined or totally left out.

The issue is that the English speaker didn’t actually translate, in the sense that they didn’t have access to the original, only the word-by-word definitions, which I don’t think is sufficient to give a full picture of the original.

I think this happened with Qiu Jin’s poetry – reading some of the early translations from eighty years ago, I can feel that the ‘translator’ didn’t actually know the original language, because in Mandarin we have multi-character words and phrases, and these were translated as individual characters, not as the full words or phrases. For example, they broke up the word ‘Japan’ – 日本 – into 日 (sun) and 本 (the original or source), then rendered it – as if it were two completely different separate words – as ‘The Sun’s Root Land’, which is very exoticising.

‘… as a poet who actually knows the language, I felt I needed to … retranslate, or just get involved …’

Yilin:

Unfortunately, this is how a lot of Classical Chinese poetry was ‘translated’ into English in the early days. And as it was often done by white academics or writers, and continues to be, there’s also this racial undertone to it which I find very upsetting. And some contributors to modern poetry in English, such as Ezra Pound, were also doing this to Chinese poetry. In other words, a lot of English modern poetry is built on this cultural appropriation of Chinese poetry.

So, as a poet who actually knows the language, I felt I needed to – in some cases – retranslate, or just get involved in poetry translation, to push back against this kind of harmful practice. It feels like people are projecting their own views of the poetry, rather than actually looking at the originals.

And bridge translation still happens in contemporary times, believe it or not – translation organisations, magazines or publishers advertise workshops to monolingual people and are like, ‘You can all become translators. We’ll give you a literal translation, then you can kind of translate.’ It’s like they don’t believe that translators who are native in a non-English source language are capable of translating by ourselves, they have to give our work to native writers in English – even if they don’t know the source language – to ‘improve’ it.

As this interview is for a translation magazine, I want to highlight that. I don’t think people are necessarily aware – especially if they don’t translate poetry – that this is widespread, and I think it’s very problematic. And when I talk to Chinese diaspora poets writing in English, many of them are horrified to hear it.

Sophia:

Yes, that’s really surprising, that’s horrible. Okay, thank you very much again for your time Yilin. We really look forward to your upcoming book.

Yilin:

Thank you so much, I really appreciate it. I’d never really interacted with Australian translators or associations before what happened with the British Museum, so I’m happy that we got to chat, it’s been so nice.